But there were other maps, printed for the wealthy. That means that multiple copies were made, and so more survive. You still paid a lot of money for them, but if enough subscribers could be found, a profit was made by the publisher.

I recently came across a series of maps from 1675, printed by John Ogilby, who describes himself as “His Majesties Cosmographer”. The sheets relating to Cheshire have been digitized and put online by Cheshire Archives. The sheets are organized as a set of strips, allowing a traveller to find their way from one major town to another. The place names are shown, though often the spellings are much changed from modern versions, along with landmarks such as bridges, churches and large houses. Compass roses are periodically included to help travellers orient themselves.

One sheet covers part of the route from London to Carlisle. The ends of the journey are covered in other sheets; the online sheet covers Darlaston in Staffordshire to Garstang in Lancashire – my part of the country.

Around my part of Lancashire, heading north up what is now the A49, the lettering goes:

Standish (Standish); Cungreve Hall (Langtree Hall); Coppen More (Coppull Moor); Whittle Bridg (Whittle Bridge); to Charley (Chorley); Whittle (Welch Whittle); Charnock Richard (Charnock Richard); Charnock More (now lost to farming); Assabing Brow (Sibbering Brow); to Eckelston (Eccleston); to Charley (Chorley); Pincock bridge (Pincock bridge); Yarrow flu: (River Yarrow); Pincock brow (Pincock Brow); Exton (Euxton – and no, it doesn’t rhyme with Euston)..

That’s pretty close to modern usage for something written down by a stranger over three centuries ago. When you consider that he would be decoding the speech of people with broad Lancashire accents, his spelling is astounding.

So I examined Ogilby’s engraving of the road I know well. 340 years after the map was published, a surprising amount of the route can still be followed by car. The format of a series of strips means that the road is straightened somewhat, but the same bends are shown. It seems that the later turnpike trusts commonly ‘improved’ existing roads rather than building new ones.

The sections going through towns are even more accurate, though often are now pedestrianised.

Here is Preston:

Ogilby’s map clearly shows the road coming up London Road from the Ribble bridge (on the previous strip), taking a left into the main street (Fishergate), then turning right up Friargate. If you are prepared to leave your car behind, you can follow the same route today.

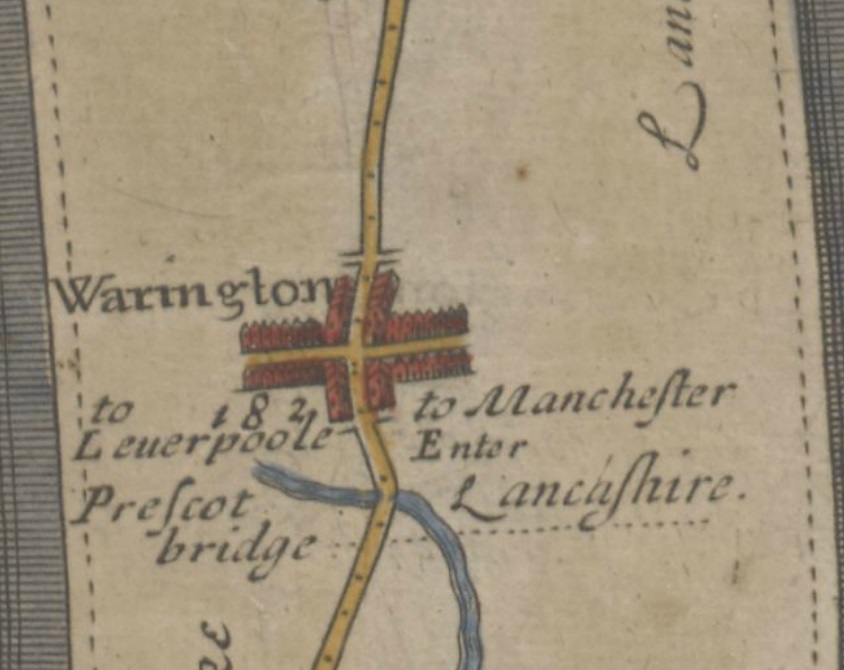

And here’s the centre of Warrington, compared with a recent map:

Note that the route through the town centre still has the same slight detour to the west. Apparently, the route was drawn by somebody who had travelled the route and had actually taken notice of things which many would overlook. John Ogilby seems to have been an outstanding cartographer, or should that be cosmographer?

My conclusion is that should you choose to walk the country using a map from 1675, you would get tired, but you would be unlikely to get lost!